Note: This is an old post on my other blog from 2017.

Raja yoga, Patanjali's 'one pointedness', that can be employed as a tool, is I believe what most attracts me, intellectually at least, to this practice and yet Ashtanga, my physical practice of choice, seems to be more from the hatha yoga tradition. Why then am I practicing hatha, which so often seems a distraction, rather than Raja yoga?

Whenever I'm troubled by this I'm reminded of Krishnamacharya's writing of Janu Sirsasana in Yoga Makaranda (Mysore 1934).....

As far as I understand it, Krishnamacharya considered Janu Sirsaana A. Raja yoga and Janu Sirssana B. Hatha yoga, funnily enough I stopped bothering with Janu B years ago.

This is the only asana Krishnamacharya mentions the distinction in the asana section but we find it all through the kriya and mudra sections ( see below).

It seems we can be practicing our asana from a Raja perspective or from a Hatha perspective. I find that very interesting. I hope I'm practicing more from a Raja perspective but I'm still very unclear of Krishnamacharya's distinction.

I suspect that Krishnamacharya got this distinction from some text, perhaps one that he mentions in his Yoga Makaranda bibliography. Krishnamacharya could converse in Sanskrit, I suspect that one of the things that attracted him to travelling all over India promoting yoga for the Maharaja of Mysore was that he got to visit all the great and small important libraries. I suspect many of the texts Krishnamacharya read are now lost to us.

Perhaps it doesn't matter, Krishnamacharya's 'Yoga for the three stages of life' is all about preparation for the householder, we're not expected to be 'real' yogis, at least not until our householder duties are complete, when we can then retire to the metaphysical forest and get down to some serious yoga. Yoga is or should be a discipline, a support for our ethics and our ethics, by simplifying, reducing, the emotional chaos of our lives, support our practice in return. It's a symbiotic relationship, our practice of yoga IS, or can be, an ethical practice. The Stoics would understand this, stoicism was and is all about training of the will.

Raja yoga, Patanjali's 'one pointedness', that can be employed as a tool, is I believe what most attracts me, intellectually at least, to this practice and yet Ashtanga, my physical practice of choice, seems to be more from the hatha yoga tradition. Why then am I practicing hatha, which so often seems a distraction, rather than Raja yoga?

Whenever I'm troubled by this I'm reminded of Krishnamacharya's writing of Janu Sirsasana in Yoga Makaranda (Mysore 1934).....

"11 Janusirsasana

This form follows the hatha yoga principles. Another form follows the raja yoga method."

As far as I understand it, Krishnamacharya considered Janu Sirsaana A. Raja yoga and Janu Sirssana B. Hatha yoga, funnily enough I stopped bothering with Janu B years ago.

It seems we can be practicing our asana from a Raja perspective or from a Hatha perspective. I find that very interesting. I hope I'm practicing more from a Raja perspective but I'm still very unclear of Krishnamacharya's distinction.

I suspect that Krishnamacharya got this distinction from some text, perhaps one that he mentions in his Yoga Makaranda bibliography. Krishnamacharya could converse in Sanskrit, I suspect that one of the things that attracted him to travelling all over India promoting yoga for the Maharaja of Mysore was that he got to visit all the great and small important libraries. I suspect many of the texts Krishnamacharya read are now lost to us.

Perhaps it doesn't matter, Krishnamacharya's 'Yoga for the three stages of life' is all about preparation for the householder, we're not expected to be 'real' yogis, at least not until our householder duties are complete, when we can then retire to the metaphysical forest and get down to some serious yoga. Yoga is or should be a discipline, a support for our ethics and our ethics, by simplifying, reducing, the emotional chaos of our lives, support our practice in return. It's a symbiotic relationship, our practice of yoga IS, or can be, an ethical practice. The Stoics would understand this, stoicism was and is all about training of the will.

*

This post marks ten years of practice and nine years of blogging about it., see this post

Is Hatha required for the Raja yoga practitioner?

|

| The Yoga Body (Hatha) |

Some argue that it is (required), that Hatha is a 'rung on the ladder' leading to the fulfilment of Raja Yoga, that the goal of Raja yoga cannot be attained WITHOUT Hatha yoga.

This argument, however, tends to be made by Hatha yogis and/or Hatha yoga writers and teachers or those confused as to where Hatha and Raja begin and end.

James Malinson and Mark Singleton's 'Roots of Yoga' is useful resource for garnering an improved understanding as to when tantra and hatha yoga concepts and practices came about. Raja yoga, it seems, got along quite nicely for hundreds of years before tantra and hatha came along*. Prana (as subtle psychic energy rather than just breath), Bindu, Kundalini, Sushumna, the Yoga body, were /are later concepts and models and not necessarily anything to do with Raja yoga.

*Patanjali's presentation of yoga may actually have become almost lost until a renewal of interest in the 13th century, no doubt as a result of the rise of Tantra/Hatha.

*Patanjali's presentation of yoga may actually have become almost lost until a renewal of interest in the 13th century, no doubt as a result of the rise of Tantra/Hatha.

|

| Roots of yoga https://www.amazon.com/Roots-Yoga-Jim-Mallinson/dp/0141394447 |

I am not suggesting in this post that one yoga methodology is correct another incorrect but rather, seeking to untangle the category mistakes, where we are talking about the objective of one approach to yoga but confusing it with the methodology associated with another that has perhaps a different objective altogether.

Here's krishnamacharya's student of thirty plus years, Srivatsa Ramaswami, responding to a question in 'Yoga beneath the surface'....

"The whole approach of yoga is to help the practitioner turn inward and understand his/her system, be it the body, the nadis, the mind, or the soul. Any of these would help to make the yogi less and less interested in the objective universe, and become more aware of himself or herself.

So, it is more a question of an inward journey or study.

Raja yoga urges the yogi to understand his/her's mind and quiet it, so that the mind 'can see the self forever'.

Hatha yoga would like the prana that is flowing outward, through the nadis to the senses to experience the exteral world, to flow inward into the sushumna and reach the sahasrara and obtain samadhi.

Kundalini yogis, with some yoga practice and intense visualisation, arouse the sleeping kundalini that obstructs the flow of prana to sushumna, and reach the Siva principie, or tatwa, in tbe sahasrara. This union of sakti with Siva is the aim of Kundalini yogis, and takes place with intense concentration within the yogi.

The same for Mantra yoga. The Sakta Mantra yogis, by intense devotion and use of the mantras, are able to arouse the kundalini and guide it through the sushumna for merger with the Siva tatwa.

All these yogas, as youu can see, are for the inward journey. All of them promise that, if you are able to reach the goal, the experience is incomparably superior to anything that one gets in this world or the world beyond, like heaven.

Kundalini yogis say that, when the ultimate union or yoga is accomplished, the yogi experiences immense bliss throughout his/her nadis.

Raja yogis such as Patanjali talk about immense peace in kaivalya.

In the Mahabharata, a great epic, it is said that the happiness one gets from fulfilment of desires, or the happiness one gets by the fulfilment of the desires in the worlds beyond, such as heaven, is, by comparison, not even a sixteenth part of the happiness one gets out of the desirelessness (vairagya) toward these objects".

Srivatsa Ramaswami yoga beneath the surface p189

Unfortunately then, all these different yoga's are called....Yoga. Not only are their methodologies different but their goals are different, one (hatha) is to achieve the immortal body and siddhis (Mallinson), another to achieve union with divine...Raja (Patanjali/Vyasa) is to attain liberation through ekigrata, applied one-pointed focus.

"Our ancients, the great rishis, followers of their sanatana dharma from the beginning of time, became experts in yama, niyama, asana, pranayama, pratyahara, dharana, dhyana, and samadhi, stopped all external movements of the mind, and through the path of raja yoga attained a high state of happiness in this world and beyond. And they continue until this day to experience this".

Krishnamacharya -Yoga Makaranda (Mysore 1934)

Krishnamacharya continues...

"But during ancient times, all were skilled yoga practitioners and therefore had good health and strength, were blessed with a long life and were able to serve society".

So Krishnamacharya starts out talking about Raja Yoga but then begins atalking bout yoga for health and strength..., the territory commonly associated with hatha yoga. Krishnamacharya seems to have assumed that there was some form of physical yoga practice way back before hatha was a glimmer in Tantra's eye.

There may well have been, it seems likely that there were other postures than the handful of seated asana Patanjali/Vyasa seem to refer to. The early ascetics clearly had tapas postures, it's not a stretch to think other postures or exercises were practiced with focus by those early yogis, if only to warm up in the morning or to shake out the limbs after a long sit.

Either way, these postures were not to unite prana, conserve bindu or force kundalini into the sushumna...., the sushumna, the yoga body concepts/models hadn't been invented/constructed back then. Nor were the yogi's concerned with achieving bliss, they had their eye on a bigger fish, bliss would have been a lower jana to pass over in seeking kaivalya, liberation, likewise the siddhis that may or may not have arisen as a distraction, a temptation....., a hindrance.

In Yoga Makaranda (Mysore 1934) Krishnamacharya at least noted where he believed one practice to be belonging to Hatha yoga another to Raja and we can assume that he is referencing the texts he mentions in his bibliography, mostly later texts. The Yoga Upanishads he references were hatha influenced, likewise the Yogayajnavalkya that Krishnamacharya had such an affection for.

Krishnamacharya was as confused as anyone else I suspect but he had a principle to work by...,

As long as a practice doesn't contradict Patanjali, go against the aims of the Yoga Sutras, then it might be considered.

In this he perhaps opened the doors to a great deal of confusion. Krishnamacharya was more than happy however to point out where practices in the hatha yoga pradipika for instance should be dismissed.

My own principle/ rule of thumb is to ask:

To what extent is this is a support for my practice, to what extent a distraction?

Where Krishnamacharya made an effort to be clear about which practices were hatha and which raja, everyone else since seems happy to have allowed them to bleed into each other such that we have the incoherent, contradictory confused situation we have today. It seems to have become quite acceptable to cherry pick from one system or another wherever our interest takes us or perhaps the marketing possibilities.

Are we then practicing asana for hatha or for raja objectives, are we seeking to attain one pointedness or to force that kundalini into the sushimna, unite apana and prana, yoke ourselves with the universal. What are we practicing for?

Even here, in our definition of the word 'Yoga' we are confused, there are multiple translations available. Generally, it seems, in the eyes of most modern practitioners Yoga is translated as 'yoke', and interpreted as union, with for example the divine/universal consciousness. For Patanjali/Vyasa..., for Raja yoga the intepretation is to 'yoke the mind', "... it entails yoking the mind on an object of concentration" (Bryant)

I'll repeat the later as this is what interests me most in yoga...

"... it entails yoking the mind on an object of concentration" (Bryant)

Ashtanga Vinyasa

Note: I consider my daily practice to be Raja yoga, Patanjali/Vyasa yoga, the form this happens to take is Ashtanga Vinyasa as presented by Krishnamacharya/Jois ( with a Vinyasa Krama interpretation). I happen to find this form, the relation of the body to the focus on the breath in silent self practice, suitable for me personally. I have never practiced with Pattabhi Jois personally and have no interest in practicing at KPJAYI, my attitude to Krishnamacharya is merely one of curiosity. I refer to Ashtanga Vinyasa in this post but my interest is in a Raja yoga free from later Hatha yoga metaphysics, it may just as well be practiced perhaps in your local studio as in an Ashtanga Shala or, my preference, our own home. I have no involvement with parampara or a guru–shishya tradition, no interest in glorifying the practice or it's teachers past or present. I am merely appreciative. Each morning, before practice I thank "...all teachers and practitioners for bringing me to and maintaining me in my practice".

What does Ashtanga Vinyasa look like to you, do you see a dynamic, fast paced, physically challenging, hot sweaty, tight bodied practice or do you see, when practiced well and modestly, stillness, do you hear the breath? For me it's the latter.

Note: personally I take my practice more slowly, modified, seeking efficiency rather than challenge and in a moderately warm room.

Pattabhi Jois, when asked, allegedly referred to the yoga he taught as Ashtanga, to reference Patanjali, his teacher Krishnamacharya's ground zero, this is pre Hatha.

Many of the criticisms directed at Ashtanga Vinyasa seem to be on account of an assumed failure by Ashtanga Vinyasa and it's teachers/practitioners to focus enough on hatha yoga concepts and practices ( although many creep in perhaps due to a lack of awareness of the distinctions/demarcation between these two yogas, as well as others).

However, Ashtanga Vinyasa is Raja yoga, the later hatha practices are not required. The asana practiced are for health, strength, fitness, concentration and need not be related to the 'Yoga body' model, the asana, the vinyasa, are also a container/a form, for the breath to be focussed upon as an object of meditation

Raja yogi's from other schools in the Krishnamacharya lineage also criticise Ashtanga Vinyasa for not giving, what they may consider, enough stress to the other limbs in Patanjali's yoga. They may have a point. However, it could also be argued that Ashtanga Vinyasa (whether practiced speedily or more slowly), in it's attention to the breath, in following the breath throughout the sixty, ninety, hundred and twenty plus minutes of practice is indeed very much in line with Patanjali's guidance. The breath is, for Patanjali /Vyasa a legitimate object of concentration and he instructs us to work on this practice, this focus on an object until samadhi arises...., which may or may not happen in this lifetime.

1.32 To prevent or deal with these nine obstacles and their four consequences, the recommendation is to make the mind one-pointed, training it how to focus on a single principle or object.

(tat pratisedha artham eka tattva abhyasah) http://www.swamij.com/

1.34 The mind is also calmed by regulating the breath, particularly attending to exhalation and the natural stilling of breath that comes from such practice.

(prachchhardana vidharanabhyam va pranayama) http://www.swamij.com/

1.39 Or by contemplating or concentrating on whatever object or principle one may like, or towards which one has a predisposition, the mind becomes stable and tranquil.

(yatha abhimata dhyanat va) http://www.swamij.com/

Notes on the 1.32 and 1.34, on breath as an object of concentration, from my preferred edition of the Yoga Sutras.

And 1:39 from the excellent Edwin Bryant's Yoga Sutras of Patanjali - with insights from the traditional commentaries.

For some, half a series of asana may be sufficient, boredom not being a distraction, for others ever more asana and series may be required to maintain interest and keep the student on the mat (something some may take advantage of rather than seeking to help overcome).

The Yoga Mat is Ashtanga Vinyasa's Zafu.

That said, the other limbs, can be a support to this practice, the yama and niyama may simplify our lives and give rise to compassion, both may help loosen our attachments and reduce distractions, they can be a support for our asana practice, just as the practice of pranayama may reduce our emotional distractions. and likewise pratyahara and just Sitting in calm abiding with the breath without the distraction of attaining a complicated asana.

At different times in our practice, teachers, fellow practitioners, attending a shala or studio, visiting Mysore, reading relevant texts, taking on more challenging asana or indeed letting go of asana may or may not be found to be a support for our practice, it may equally be that merely attending to the breath, alone and at home, practicing modestly, is more than sufficient.

Patanjali/Vyasa's eight limb (ashtanga) Yoga is a clear, straight forward path/methodology but hard if not near impossible to follow, to stick to/with, there are seemingly endless distractions. The yama/niyama are there to help us with these distractions. Krishnamacharya stressed that the yama/niyama should be engaged with from the beginning. Unfortunately it's often suggest that the yama and niyama can come later, after the asana or late into asana practice.

Asana, rather than being a tool to overcome distraction, to help lead us towards one-pointedness, has for many become the biggest distraction of all, perhaps as a result of this lack of attention to the yamas and niyamas (whether of our own culture/tradition or as outlined by Patanaji). Our inner craving for distraction has been fed upon by the market, we need it seems ever better alignment, more flow, more visualisation, we need ever more anatomy awareness or more understanding of this allegedly related concept/model from the hatha tradition, we need more historical knowledge.

Of course we need none of these. We can sit on the edge a chair and follow the breath, or we can use Ashtanga vinyasa as a tool and move from one asana to the next with enough awareness of anatomy perhaps to keep us safe while bringing our attention constantly back to the breath, whether we practice half a series or six. Nothing else is required.

If samadhi arrises in this lifetime, then we'll need to go back to Patanjali and see what comes next but for most of us, "ekam-inhale....".

Whether we ever attain samadhi or not we can perhaps tread more lightly in the world, be of service, live healthier, calmer lives with focus and concentration that we may direct where we feel is most appropriate. If samadhi arises, so be it if not this perhaps is sufficient.... for this lifetime.

UPDATE:

from the comments

Shaz2 March 2017 at 22:20

Interesting post, thank you. I am still trying to figure it out.

What would you say then of a lot of Astanga teachers that teach the movement of prana in asana? So, the 'alignment' is the bringing together of prana and apana, with their associated physical spiralling actions? Richard Freeman and many of his students teach this. Is this then the 'bleeding over' of hatha methodology into the kriya yoga / raja yoga?

And what about the enormous emphasis on mula bandha? Mula bandha is also very much about getting energy into the sushumna.

Replies

Anthony Grim Hall - 3 March 2017 at 09:17

"Interesting post, thank you. I am still trying to figure it out". Me too.

"What would you say then of a lot of Astanga teachers that teach the movement of prana in asana?" That's what the post is Shaz, my response to this.

Raja and Hatha are separated by hundreds of years Shaz, it's like comparing Plutarch with Roger Bacon, we might call both Philosophers, practicing philosophy both engaged in the search for knowledge but they are as different as chalk and cheese. and I don't fancy attempting to write on a blackboard with a stick of edam or put chalk in my cheese and tomato sandwich.

As I mention above Krishnamacharya was no doubt as confused as everyone else as to Hatha and Raja practices, while emphasising Patanjali and the yoga sutras (Raja) he leaned toward the Yogayajnavalkya a tantra/hatha influenced text. He included hatha mudras and kriyas in his Yoga Makaranda, though distinguishing between them which he believed to belong to hatha and which raja. He seemed to feel that one could bring in certain hatha practices either for the associated healt benefits and/or as a support for Raja yoga. Pattabhi Jois did the same, as you say, stressing the bandhas.

Am I suggesting we abandon bandha practice, I'm undecided but leaning towards the idea that we can abandon the tantra metaphysics, the hatha goals and yet still chose to include certain practices that have clear benefits for our physical practice. So we can perhaps abandon the hatha concept of prana/apana ( for Patanjali, prana seems just to have referred to the breath, not a subtle psychic energy) and yet hold onto the muscular aspect of bandhas in say their support for the spine in our asana practice.

Re Richard Freeman. If you're a follower of this blog you'll know I love Richard, I find his visualisations beneficial at times for moving in and out of as well as holding postures, I don't however take on board the hatha ideas he writes about concerning prana/apana, kundalini, sushumna or seeking bliss. Richard is interesting in that, as he is the first to say, he brings together several traditions of yoga into the Ashtanga Vinyasa he teaches. Richard studied several different forms of yoga for many years before practicing with Patabbhi Jois.

Is the idea of 'Ashtanga without Hatha', throwing a whole bath full of babies out with the bathwater, possibly but we are in an environment where the market will latch on to anything it thinks it can sell and promote.

This post is asking if it's still possible to separate out Hatha from Raja. If it's possible today to have an asana practice with a Raja yoga intention without recourse to the tantra metaphysics on which hatha practices are based.

If the answer is yes, and I believe it is, then we can perhaps look at individual hatha practices and, as with the bandhas, consider if their practice is beneficial without regard to the conceptual model which gave rise to them.

But again, this post is not intended to be critical of Hatha or of Tantra, it could equally be a post about practicing Hatha without concern for Patanjali/Vyasa, Samkhya and Raja yoga. Or the even more interesting question perhaps as to whether it's Patanajali/Vyasa's Raja yoga is conceivable without a Buddhist influence.

Appendix

Note: While I focus on Krishnamacharya here in the appendix, to illustrate the distinction he made between hatha and raja yoga practices, this post is not concerned with the question of what or how Krishnamacharya practiced ( or Jois for that matter) but whether Raja can be practiced today without recourse to hatha practices

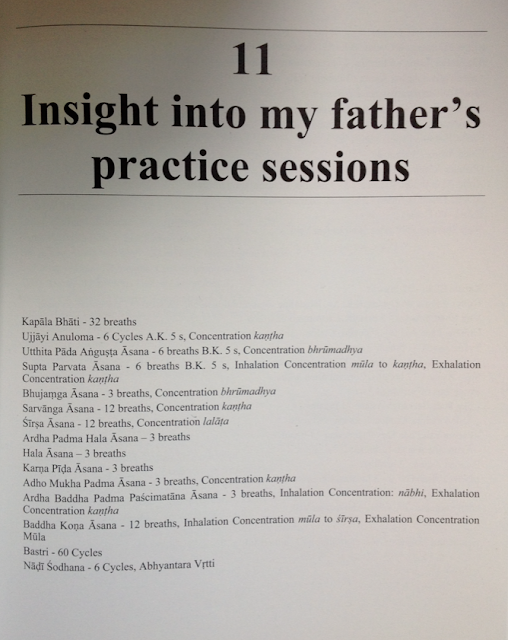

1. Kriya and Mudra practices Krishnamacharya indicated as belonging to Raja Yoga in his Yoga Makaranda ( Mysore 1934)

*

In Yoga Makaranda, Krishnamacharya lists Kiriyas and Mudras and notes which belong to Raja and which to Hatha yoga. I find it interesting and useful to separate out the different practices and list them under their different traditions, we may get a feel for what seems to characterise each.

Krishnamacharya even makes this distinction in his instructions for janu Sirsasana.

As far as other asana go, we might look at how Pattabhi Jois (Krishnamacharya's assistant for a time) taught asana, perhaps reflecting how Krishnamacharya himself taught the boys of the palace with the focus on strength, health fitness, concentration and contrast it with krishnamacharya's own instruction in Yoga Makaranda, the longer stays, the kumbhakas, perhaps there is an implied distinction between asana for strength and asana for spiritual progress along with the benefits outline that may be considered asana for health.

Personally I'm no longer that interested the practices outlined below. We should remember too that Krishnamacharya was but one scholar, one authority and most likely flawed by the limitations of his research and the information available to him at that time.

****

All quotes below from Krishnamacharya's Yoga Makaranda (Mysore 1934)

There are many types of this yoga — 1. hatha yoga, 2. mantra yoga, 3. laya yoga, 4. raja yoga.

Hatha yoga focusses mainly on descriptions of the methods for doing asanas.

Raja yoga teaches the means to improve the skills and talents of the mind through the processes of dharana and dhyana. It also explains how to bring the eleven indriyas under control and stop their activities in the third eye (the eye of wisdom), the ajn ̃a cakra, or the thousand-petalled lotus position (that is turn their attention inward and not outward) and describes how to see the jivatma, the paramatma and all the states of the universe. But even here it is mentioned that to clean the nadis it is necessary to follow the pranayama kramas.

Asana and pranayama are initially extremely important. But if one wants 21 to master asana and pranayama, it is essential to bring the indriyas under one’s control.

Yoga consists of eight angas which are yama, niyama, asana, pranayama, pratyahara, dharana, dhyana and samadhi.

I. Dhauti Kriya

1. Antar Dhauti: This is of four types: vata sara dhauti, vari sara dhauti, vanhi sara dhauti, bahish kritham dhauti.

(a) Vata Sara Dhauti: For this, first hold the mouth like a crow’s beak and gradually suck in the air. Then close the mouth and swallow the air that was sucked in. After this, allowing the air to occupy the stomach, swirl it this way and that in waves as though washing the stomach. Then send it out of the body through the anus or the nose.

Practising this just once isn’t enough to expel the sucked-in air through the anus. Practise this for several days without fail, repeating the activity at least 25 times daily. Then, after a few days it will become possible to expel the air through the anal passage.

Those who do not have the time for this can expel the air through recaka or exhalation of the air out through the nose slowly and care- fully. This will give very good benefits. This vata sara dhauti belongs to raja yoga.

(c) Vanhi Sara Dhauti: The stomach along with the navel should be pulled in to touch and press against (stick to) the spine and then should be pushed forward again. Repeat this several times. While pulling the stomach in, do recaka kumbhaka and while pushing it out do puraka kumbhaka. Practise this before eating. If you want to do this after eating, wait at least three hours. Otherwise it will be dangerous. This exercise needs to be practised daily, repeating it 84 times in a day. This belongs to raja yoga.

3.6. SECTION ON THE INVESTIGATION OF SHATKRIYAS 39

kumbhaka. Practise this before eating. If you want to do this after eating, wait at least three hours. Otherwise it will be dangerous. This exercise needs to be practised daily, repeating it 84 times in a day. This belongs to raja yoga.

II Basti Kriya

2. Sthala Basti: Sit in pascimottanasana. Through aswini mudra draw in the vayu and push it out and turn the stomach in all four directions.

Benefit: Constipation, indigestion — such diseases will be destroyed. It will increase jathara agni. This is raja yoga.

2. Vamakrama Kapalabhati Kriya: (left side) Draw in (inhale) the air through the left nostril and exhale it out through the right nostril. Then draw in the air through the right nostril and exhale it out through the left nostril. After you do this four times, draw in clean water through the left nostril. Lift the face up, press the left nostril with the finger, tilt the head slightly to the right side and spill out the water through the right nostril. In a similar manner, the water taken in through the right nostril should be expelled or spilled out through the left nostril.

Benefit: Dripping phlegm diseases (running nose) will be prevented. It will develop the strength of the indriyas to smell even the most subtle smell. This is raja yoga.

IV. Nauli Kriya

The nerves of the lower abdomen are pulled into the stomach and are then rapidly turned around this way and that, to the left and right sides, all around the stomach.

Benefit: Removes all diseases and strengthens digestive power. This is raja yoga.

V. Trataka Kriya

Fix the gaze at one point or object without moving or blinking the eye until it starts to tear.

Benefit: Removes all diseases of the eye; gives good eyesight. Not only that, it develops the power to become adept at sambhavi mudra and will also prevent long sightedness. This is raja yoga.

VI. Kapalabhati Kriya

This is of three types: vyut krama, vama krama and cit krama.

1. Vyutkrama Kapalabhati Kriya: Draw in water through the

nostril and send it out through the mouth. This is raja yoga.

2. Vamakrama Kapalabhati Kriya: (left side) Draw in (inhale) the air through the left nostril and exhale it out through the right nostril. Then draw in the air through the right nostril and exhale it out through the left nostril. After you do this four times, draw in clean water through the left nostril. Lift the face up, press the left nostril with the finger, tilt the head slightly to the right side and spill out the water through the right nostril. In a similar manner, the water taken in through the right nostril should be expelled or spilled out through the left nostril.

Benefit: Dripping phlegm diseases (running nose) will be prevented. It will develop the strength of the indriyas to smell even the most subtle smell. This is raja yoga.

Mudras

7. Mahadeva Mudra: Sit in mula bandha mudra and do kumbhaka in uddiyana bandha.

Benefit: This will increase the jathara agni and you will get the animadi guna siddhi — one of the eight siddhis which is the quality of becoming as minute as an atom. This belongs to raja yoga.

9. Viparita Karani Mudra: Keeping the head on the ground, lift the legs up and hold the entire body straight without bending or curving the body in any direction. This is raja yoga.

13. Tataka Mudra: Sit in pascimottanasana and push the stomach for- ward. This is raja yoga.

15. Sambhavi Mudra: Due to the strength of the traataka abhyasa men- tioned in the shatkriyas, after the eyes have teared profusely, fix the gaze on the mid-brow.

Benefit: This gives rise to ekagrata citta and gives dhyana siddhi. This is raja yoga.

16. Aswini Mudra: Repeatedly close and open the anal opening many times.

Benefit: Cures diseases of the rectum, will render physical strength and sharpness of the intellect, awakens the power of kundalini and conquers untimely death. This is raja yoga.

19. Mathangini Mudra: Stand in water up to the neck. Through the nostrils, draw in water and spit it out through the mouth. Then take in water through the mouth and expel it out through the nose. This is raja yoga.

20. Bhujangini Mudra: Stay in bhujangasana, stretch the neck out in front and according to vata sara krama, pull in the outside air and do puraka kumbhaka.

Benefit: This will remove diseases like indigestion, agni mandam (low agni), stop stomach pain and leave you happy. This is raja yoga.

11 Janusirsasana

This form follows the hatha yoga principles. Another form follows the raja yoga method. The practitioner should learn the di erence. First, take either leg and extend it straight out in front. Keep the heel pressed firmly on the floor with the toes pointing upward. That is, the leg should not lean to either side. The base (back) of the knee should be pressed against the ground. Fold the other leg and place the heel against the genitals, with the area above the knee (the thigh) placed straight against the hip. That is, arrange the straight leg which has been extended in front and the folded leg so that together they form an “L”. Up to this point, there is no di erence between the practice of the hatha yogi and the raja yogi.

For the hatha yoga practitioner, the heel of the bent leg should be pressed firmly between the rectum and the scrotum. Tightly clasp the extended foot with both hands, raise the head and do puraka kumbhaka. Remain in this position for some time and then, doing recaka, lower the head and place the face onto the knee of the outstretched leg. While doing this, do not pull the breath in. It may be exhaled. After this, raise the head and do puraka. Repeat this on the other side following the rules mentioned above.

The raja yogi should place the back of the sole of the folded leg between the scrotum and the genitals. Now practise following the other rules described above for the hatha yogis. There are 22 vinyasas for janusirsasana. Please note carefully that all parts of the outstretched leg and the folded leg should touch the floor. While holding the feet with the hands, pull and clasp the feet tightly. Keep the head or face or nose on top of the kneecap and remain in this sthiti from 5 minutes up to half an hour. If it is not possible to stay in recaka for that long, raise the head in between, do puraka kumbhaka and then, doing recaka, place the head back down on the knee. While keeping the head lowered onto the knee, puraka kumbhaka should not be done. This rule must be followed in all asanas.

While practising this asana, however much the stomach is pulled in, there will be that much increase in the benefits received. While practising this, after exhaling the breath, hold the breath firmly. Without worrying about why this is so di⇥cult, pull in the stomach beginning with the navel, keep the attention focussed on all the nadis in and near the rectal and the genital areas and pull these upwards — if you do the asana in this way, not only will all urinary diseases, diabetes and such diseases disappear, but wet dreams will stop, the viryam will thicken and the entire body will become strong.

Whoever is unable to pull in the nadis or the stomach may ignore just those instructions and follow the instructions mentioned earlier to the extent possible. Keep the nadis in and near the rectal and genital areas pulled up, the stomach pulled in and hold the prana vayu steady. Anybody with the power to practise this will very soon be free of disease and will get virya balam. Leaving this aside, if you follow the rules according to your capability, you will gradually attain the benefits mentioned below.

2. Kriya and Mudra practices Krishnamacharya indicated as belonging to Hatha or Laya Yoga in his Yoga Makaranda (Mysore 1934)

(d) Bahish Kritha Dhauti:

Position the mouth like a crow’s beak and suck in the air to the extent possible. Hold the air in (kumbhaka) and then exhale it out (recaka) through the nostril. This is only for those who are beginning the practice of recaka kumbhaka. Repeat this 25 times a day. This has to be done either before eating in the morning or before eating in the evening. If one keeps increasing the practice of this correctly, it develops the ability to hold the breath (kumbhaka) for long periods. Not only that, it will automatically become possible to expel the air through the anal opening. Once you begin to expel the air through the anal opening, you should not then try to exhale it out through the nose. Through this practice, after acquiring the ability to hold the breath for 1.5 hours, proceed as follows: Standing in water up to the navel, very carefully and cautiously push out the large intestine which is the sakti nadi located in the lower abdomen up to the muladhara cakra through the anal opening. Wash it with water until it is clean and then push it back inside through the same anal opening.

Warning: This kriya is only for hatha yogis and not for raja yogis, laya yogis or mantra yogis.

Jihwa Dhauti:

Scrub the tongue vigourously using the three fingers of the right hand excluding the thumb and little finger. Spit out all the phlegm that comes out while rubbing the tongue. Afterwards, wash the tongue with water, gargle and rinse the mouth. Then rub cow’s butter on the tongue. After this, with a small iron tong, hold the tip of the tongue lightly and little by little pull it out. This is only for hatha yogis.

Jala Basti: Stand in water up to the navel. Then get into utkatasana and through the strength of kumbhaka, force the water in through the open- ing of the anal canal. Practise this as described and before twelve repeti- tions, su⇥cient water will reach the lower abdomen. After this, following the krama, push the water that is in the abdomen little by little back out through the anal opening. This should be done three times a day.

Benefit: Diabetes, urinary diseases, obstruction of bowels — such diseases caused by bad apana vayu will be removed. One acquires a handsome beautiful physical appearance and the body develops a shine and beauty like that of Manmada. This belongs to hatha yoga.

III. Neti Kriya

Take one span (the length between the thumb and little finger) of thin thread. Suck it in through the nostril and hold the two ends of the thread with the two hands after one end comes out of the mouth. Very carefully (caution!) pull it up and down about 10 — 12 times. This thread should then be removed through the mouth.

Benefit: Removes many types of kapha diseases. It will give good eyesight and will help to become adept at khecari mudra. This is hatha yoga.

Citkrama Kapalabhati Kriya: Take water in through the mouth, swallow it and then expel it out through the nose. This is to be repeated twenty-three times.

Benefit: This will remove diseases of phlegm, will also prevent old age, and will give lustre or brilliance to the body. This is hatha yoga.

All the kapalabhati kriyas should be done with clean, cool (unheated) water. The superior time for practising these kriyas is early in the morning before sunrise. For the first fifteen days of practising these kapalabhati kriyas, there will be a burning sensation in the nose, mouth and throat and you will develop a little phlegm or congestion. Ignoring these symptoms, very faithfully follow the instructions and practise the kriyas. All the benefits mentioned above will be experienced very quickly.

Mulabandha Mudra:

With the left heel, firmly press the kandasthana which is between the rectum and the genitals and pull the heel in tightly in order to close the anus. Pull in the stomach firmly and press it against the bones in the back (the spine). Bring in the right heel and place it on top of the genitals. This is in hatha yoga.

Khecari Mudra:

After first learning the yoga marmas with the help of a satguru who is still practising this, cut 1/12 of one angula measure (width of one hair) of the thin seed of skin at the bottom of the tongue with a sharp knife. Apply a well-powdered paste of sainthava lavanam salt (rock salt) on the area of the cut. Rub cow’s butter on both sides of the tongue, and holding the tip of the tongue with a small iron tong, pull the tongue out carefully, little by little. Repeat this (the pulling) every day. Once a week, as mentioned above, cut the seed of flesh at the base of the tongue very carefully. Practise this for three years. The tongue will lengthen and will easily be able to touch the middle of the eyebrows. After it lengthens this much, fold it inside the mouth, keep it in the cavity which is alongside the base of the inner tongue and fix the gaze on the mid-brow.

Benefit: Hunger and thirst subside without loss of body strength and with- out allowing room in the body for any disease. If practised daily, the body develops a lustre in a few days and one quickly reaches the state of samadhi and drinks the divine nectar. This belongs to hatha yoga.

(b) Vajroli Mudra:

Form 2: Take a 12 angula long thin glass pipette or lead pipe and through the genital opening insert it and remove it daily, increasing the amount of insertion by one angula each day. After you are able to practise inserting the pipe for a length of twelve angulas, draw in the outside air through such an opening in the genitals. After practising this, eventually draw in milk and then water and then push them out of the body. This is hatha yoga.

Manduka Mudra:

Keep the mouth closed and fold the tip of the tongue up to the top palate and after this keep moving it this way and that. Catch the nectar dripping from the upper part of the root of the tongue and swallow it. This is hatha yoga.

Pasini Mudra:

Take the two legs and place them behind the neck. Extend the arms, and with the support of the outstretched hands placed on the ground, raise the body.

Benefit: Kundalini being kindled nourishes the body. This is hatha yoga.

Kaka Mudra:

Hold the mouth like a crow’s beak and inhale and pull

in the outside air into the stomach.

Benefit: All diseases will be eliminated and you will have a long life like a

crow. This is hatha yoga.

Laya yoga

(b) Vari Sara Dhauti: Pure hot water or cold water should be drunk until the stomach is full and the water reaches almost up to the neck. Swirl the water in the stomach this way and that, up and down. Then pull in the stomach forcefully and push it out, sending the water out through the anal opening. This belongs to laya yoga. This kriya can be mastered by practising it several times daily.